By Kyle Brandys

“Let us take a sightseeing tour,” says the bicycling journalist Herbsaint Sazerac (Owen Wilson) to viewer in Wes Anderson’s latest film The French Dispatch. Yes, let’s. The fictional town of Ennui-Sur-Blasé is introduced via an early segment of the film, aptly titled “The Cycling Reporter.” As if the seat underneath each audience member has been hoisted and fixed upon Sazerac’s red handlebars, we glimpse with the help of Sazerac’s sardonic narration the town he holds so beloved. Cobblestoned streets. A dingy underground railroad system. A cool blue night intruded upon by the dazzling, yellowish glow of the corner café, Le Sans Blague. There is much to be seen. Perhaps too much for some. Before long, one may be inclined to spring for the rewind button on their remote controller—like a driver who, having glimpsed something in their peripheral vision, cranes their head backwards at the missed attraction.

Figure 1. Sazerac rides throughout Ennui.

Sazerac ends his article with the poetic proclamation: “All grand beauties withhold their deepest secrets.” It is a phrase that hints that many return trips (or a detailed guide) to the film may be needed to fully see everything Ennui has to offer. And as Sazerac’s quote claims, hidden complexities and darker truths do indeed lie underneath the beautiful visage of Ennui-Sur-Blasé.

Standard for the world of Wes Anderson: a cornucopia of visual citations to other works cherished by Wes Anderson. In lieu of one overarching narrative, these allusions form the building blocks of The French Dispatch, acting as key “landmarks” to catch along the journey (seasoned travelers will indeed find themselves pointing with recognition at a recognizable ode to another from film, oohing at a telltale reference to a famous writer). This film more than any other of Wes Anderson’s is a love letter to his eclectic tastes: most notably, The New Yorker magazine and French cinema.

It should be said that these homages are not exactly “withheld”: the film’s inspirations are worn very much on its sleeve. Wes Anderson has even prepared a wealth of materials that details many of the film’s influences. This includes: a book, An Editor’s Burial, prepared by Anderson, containing 14 stories from famous expatriate writers; the end credits of the film, which acts as dedication page to the writers from The New Yorker, and a list of 32 films that inspired Anderson to make the film.[1] Navigating these documents, however due to their quantity and intricacy, may also lead one to feeling lost in a foreign city. What the allusions indicate for the film’s themes and many theses is also not entirely revealed by the director. In the spirit of Sazerac’s segment, this article will act as tour guide to the film, parsing a small selection of the homages, in an effort to decipher some of the “grand beauties” of the town of Ennui and The French Dispatch.[2]

Our first stop takes us to the home of The French Dispatch of the Liberty, Kansas Evening Sun (one of the film’s first shots). The building that houses the publication stands tall in a town plaza of Ennui. The viewer watches as a mustachioed waiter, after delicately preparing a tray full of mostly caffeinated beverages climbs via crooked stairs, hidden corridors, and an antiquated pulley system, to the top floor of the building. It should be noted that his ascent although laborious may well be the last climb conducted by the waiter; the storied editor of the publication, Arthur Howitzer Jr (Bill Murray), will die this very day, effectively closing the magazine, and ending any need for future meals to be served at The French Dispatch.

This introductory sequence is a reproduction of a scene from Jacques Tati’s famous film Mon Oncle (My Uncle, 1958), in which Tati’s signature character Monsieur Hulot climbs the steps of a nearly identical building in Paris. Just as with the waiter, in a static wide shot, we watch through many windows—small, big, round, and square—a humorous traversal of the building by Hulot. During the passage, Hulot is rhythmically obscured from the viewer’s gaze; the eye flicks to and fro trying to find him, when the appearance of brown shoes in a hatch like opening of the building or his iconic hat glimpsed in a small portrait sized aperture, rematerializes the character, permitting his journey to continue.

-

Figure 2. The waiter makes his ascent to the office of The French Dispatch -

Figure 3. Hulot climbs to his apartment in Mon Oncle.

The waiter traces the iconic Monsieur Hulot’s steps, and in doing so, follows in the more thematic footprints of Mon Oncle. The house in Mon Oncle is aging, decrepit, and rustic, already a relic of the past. The time and effort taken to conquer the summits of the two buildings demonstrates a clever visual gag while effectively communicating the films’ themes of a stubborn rejection of modernity (and elevators). An ironic and impressive layering of beginnings and endings is depicted: this first sequence in The French Dispatch introduces the viewer to the publication, while announcing its immediate demise—and on top continues Tati’s themes of obsolescence

Squint your eyes through various chapters throughout The French Dispatch and you will find mischievous caped schoolboys running rampant throughout the town, a deliberate echoing of Jean Vigo’s Zéro de conduite (Zero for Conduct, 1933). Like The French Dispatch, Zéro de conduite, is less a narrative film and more textured exploration of a town’s inhabitants. Zéro de conduite’s more modest scope centers on the misadventures of young students in a boarding school. The appearance of a similar gang, “marauding choir boys half-drunk on the blood of Christ,” in The French Dispatch is given an undoubtedly solemn tint due to Vigo’s untimely death in 1934, at only 29 years old. It as if these children, having been refused a chance to grow old due to Vigo’s death, have been frozen in time, stuck in Ennui. (The nesting doll structure of The French Dispatch also continues to manifest: The camera’s capturing of rebellious schoolchildren running at full sprint simultaneously pays homage to François Truffaut’s Les quatre cents Coups/The 400 Blows, which first emulated Vigo’s film in 1959.)[3]

Painted upon a wall by protesters in the Ennui of 1968 are the words “Les enfants sont grognons” (translating in English to “the children are grumpy”). It is fitting that it is among the disenchanted adolescents of the segment“Revisions to a Manifesto” that François Truffaut’s presence can best be felt. The infantilization found in this slogan ties The French Dispatch to Truffaut’s 1968 film Baisers volés (Stolen Kisses), shot during the very same protest movement, the events of May 1968 in France. Baisers volés, a sequel to Les quatre cents Coups, shows Truffaut’s most famous protagonist Antoine Doinel amidst a crisis of youthful precarity, unsure of his place in the world as he enters into adulthood.

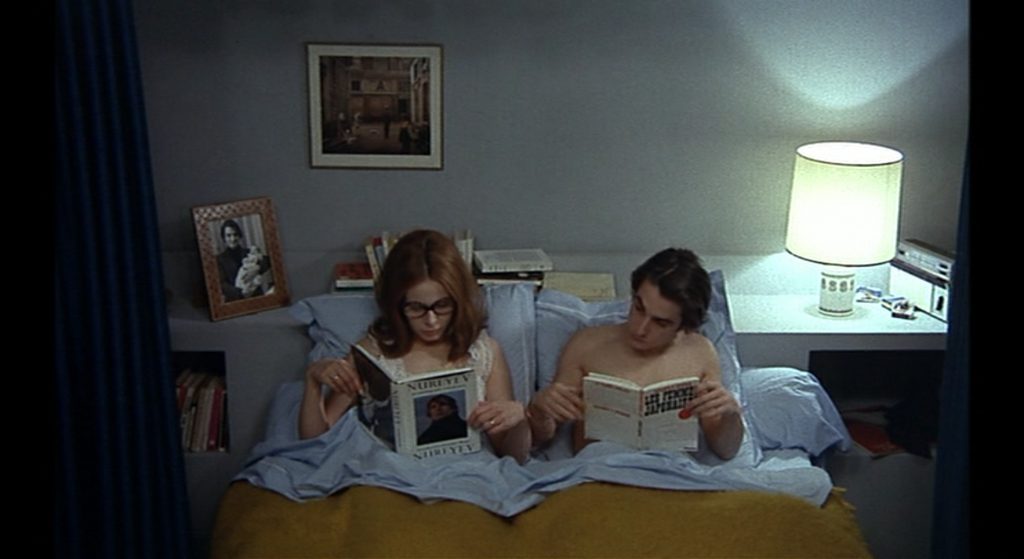

Doinel’s apathy in Baisers volés towards the protests admittedly clashes with the main vehicle of “Revisions to a Manifesto”: the charming, messy haired Zeffirelli (Timothée Chalamet), leader of the Ennui student revolts. Nevertheless, despite the disparity in philosophies towards political action, there are many ties between the two characters. Doinel and Zeffirelli, besides a physical resemblance and a fondness for grey blazers are inexorable conductors of juvenile energy and restlessness (An observation made by Frances McDormand’s Mrs. Krementz that the youth in the town display a “touching narcissism” could certainly be applied to either character.)[4] The two young men’s romantic escapades also notably include the pursuit of older women. A shot of Zeffirelli in bed with the much older journalist Mrs. Krementz very much mirrors a famous shot from the next Doinel adventure, Domicile conjugal (Bed and Board, François Truffaut, 1970). However, where Doinel was given the luxury to age throughout future sequels, the more tragic twists and turns of Zeffirelli’s story means his youthful spirit can only be eternalized via the fronts of t-shirts, newspapers, and cigarette packages.

-

Figure 4. Ms. Krementz and Zeffirelli edit their projects. -

Figure 5. Antoine Doinel and Christine Darbon in Domicile conjugal.

Our final stop is perhaps The French Dispatch’s most layered and complicated homage. In the home of the B family, Zeffirelli, towel concealing his frizzy hair, pens a manifesto in a bathtub while arguing with Mrs. Krementz. This is an invocation of J.D. Salinger’s Franny and Zooey, in which the titular Zooey Glass—also in a bathtub— reads a script and a letter from his brother while quarrelling with his mother. An important note about this particular allusion: this is not the first time the scene has been featured in a Wes Anderson film. The Royal Tenenbaums (Wes Anderson, 2001) paid homage to Franny and Zooey, when Margot Tenenbaum, soaking in a bathtub, feuded with her mom over her marital problems. The French Dispatch’s latest trip to the well (or bathtub) seems to come with a bittersweet spirit. In a film of nostalgic desire for past texts, by finally turning to himself, the scene predicts Anderson’s oeuvre as one day joining these other works, remaining behind only as lingering cinematic memory in Ennui.

Spend enough time in Ennui, it becomes clear that the film is as much scenic guide as ghost tour. To traverse the town is to walk through graveyards and haunted houses (Truffaut, Tati, Salinger, reduced to mere specters). There is a solemnity to The French Dispatch’s invocations that resonate with the film’s overarching themes of death and nostalgia—the story is framed around an editor’s burial, after all. A fear that Anderson’s idiosyncratic delights may be growing more irrelevant seems to lurk underneath the film’s surface.[5] Nevertheless, contemporary concerns for the declining status of print journalism—including of course The New Yorker—and a box office excessively dominated by franchise films may puncture through the film’s period setting but still be kept at arm’s length.

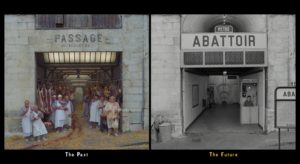

Figure 6. Past and Future in The French Dispatch.

An early moment in “The Cycling Reporter” depicts various districts and settings from Ennui in split screen (and in both black and white and color): the left side of the screen for “The Past,” the right for “The Future.” It would be a natural assumption to make that Ennui’s past would be painted in monochrome, color for Ennui’s future. This, however, is not the case. The past and present trade hues with each other, as if taking turns in a polite game of hopscotch. Past in black and white. Present in color. Past suddenly in color. Present now in black and white. This sets the stage for The French Dispatch’s strongest moments, where select scenes set in Ennui’s past are suddenly bathed in Anderson’s signature pastel palette: the constraints of time are unable to withstand the film’s bursts of emotional climaxes.

While death is not absent in Ennui (far from it), such play with temporality suggests Ennui may exist as a form of limbo, where history is more of a whimsical game than rigorous construct.[6] Fears of obsoletion and outside concerns may threaten but never entirely defeat the charming anachronisms of the town. The publication of The French Dispatch may be shown as ending in its first few frames, but it is subsequently reborn in the rest (the final scene also suggests its spirit very much will live on in the magazine’s contributors). Disparate elements—the house from Mon Oncle, J.D. Salinger’s bathtub, Vigo’s schoolchildren—are plucked out of time, stretched and sculpted into new but familiar shapes, so they may last a little longer, in the fictional town of Ennui.

Kyle Brandys is an alumnus from the University of North Georgia and a graduate of University of Toronto’s Master’s program in Cinema Studies.

[1] See, https://thefilmstage.com/32-films-that-inspired-wes-andersons-the-french-dispatch/

[2] Due to Anderson’s extensive explanation for The New Yorker’s influence on the film, this article will mainly cover more obscure references.

[3] Anderson and interviewer Susan Morrison make brief reference to the link between these caped children and Vigo and Truffaut films in The Editor’s Burial. David Brendel, ed., The Editor’s Burial (London: Pushkin Press, 2021), 12.

[4] The quotation originates from the inspiration behind Mrs. Krementz and this section, The New Yorker’s publication of Mavis Gallant’s observations from the May 1968 Protests. Mavis Gallant, “The Events in May: A Paris Notebook~I”, The New Yorker, September 14, 1968.

[5] The term Ennui itself refers to a malaise brought about by dissatisfaction.

[6] Besides “Revisions to a Manifesto,” Anderson says he is not sure when any of the other segments are set. David Brendel, ed., The Editor’s Burial, 13.