During the postwar renaissance of avant-garde film in the United States, Frank Stauffacher established the Art in Cinema series at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, an experimental film program that exhibited eleven series over the course of nine years, and ended when he tragically died of a brain tumor in 1955. Although this series is often referenced by film historians, his curation process has been vastly underappreciated and understudied. Stauffacher’s passion for how the visual arts intersect with cinematic form shaped his Art in Cinema program, through which he defined the experimental film genre for American audiences and paved the way for future film societies worldwide.

During the postwar renaissance of avant-garde film in the United States, Frank Stauffacher established the Art in Cinema series at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, an experimental film program that exhibited eleven series over the course of nine years, and ended when he tragically died of a brain tumor in 1955. Although this series is often referenced by film historians, his curation process has been vastly underappreciated and understudied. Stauffacher’s passion for how the visual arts intersect with cinematic form shaped his Art in Cinema program, through which he defined the experimental film genre for American audiences and paved the way for future film societies worldwide.

As a former art student at the ArtCenter in Los Angeles in the mid-thirties, Stauffacher held a tremendous appreciation for and knowledge of the art world (MacDonald, 2006). The location of his alma mater naturally ensured that he was exposed to the world of filmmaking, igniting his passion for the parallels between art and cinema. Back in his hometown of San Francisco, and after World War II, he decided to give up commercial art in the advertising world for a 16mm camera and studio space (Stauffacher Solomon, 2005). Stauffacher made his first short documentary titled Bicycle Polo at San Mateo in 1942. A few short years later, as he continued to make his own films, he began designing the first Art in Cinema series at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art along with his friend Richard Foster (Ghetti, n.d.).

Frank Stauffacher took a pedagogical approach to assembling the Art in Cinema program series. No one had ever assembled an experimental film exhibition before; therefore, there were no existing philosophies or theories on why it was important, where it belonged in the art world, or how anyone should go about curating a selection for an audience. Throughout the program’s history, he consistently consulted with a small committee of varying members, doing his best to keep an objective viewpoint regarding film selection. As stated in the program announcement for Art in Cinema’s first series, the group aimed to achieve a few different objectives. First, that the films exhibited would reveal the relationship of the avant-garde film with other art, specifically sculpture, painting, and poetry. Second, that it would promote interest in film as a creative medium and foster an engaged and creative audience. And furthermore, that it would assist the current unknown filmmakers of the genre with more distribution pathways (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art & Stauffacher, 1946).

In attempting this, Stauffacher showcased feature films, shorts, animations, and documentaries, giving his audience a wide array of cinema touched or defined by the experimental genre (MacDonald, 2006). In order to educate and prime his audience for more contemporary material, Frank’s first and second program series gave them a history of experimental film, featuring many early lesser-known works peppered with the more prominent, like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Un Chien Andalou, and A Trip to the Moon (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art & Stauffacher, F. (presumed), 1946; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art & Stauffacher, F. (presumed), 1947). His third series featured contemporary experimental work, roughly half hailing from artists in the San Francisco area, regardless of whether it came from an independent or studio production. Art in Cinema gained so much acclaim and popularity that attendance averaged around 500 per night and up to 800 per night at additional screenings at University of California, Berkley (MacDonald, 2010). This trend continued throughout most of the existence of Art in Cinema, additionally featuring numerous European award winners, old classics, and new works, all showcasing the assertive, exploratory choices that defined the genre (MacDonald, 2006).

In attempting this, Stauffacher showcased feature films, shorts, animations, and documentaries, giving his audience a wide array of cinema touched or defined by the experimental genre (MacDonald, 2006). In order to educate and prime his audience for more contemporary material, Frank’s first and second program series gave them a history of experimental film, featuring many early lesser-known works peppered with the more prominent, like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Un Chien Andalou, and A Trip to the Moon (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art & Stauffacher, F. (presumed), 1946; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art & Stauffacher, F. (presumed), 1947). His third series featured contemporary experimental work, roughly half hailing from artists in the San Francisco area, regardless of whether it came from an independent or studio production. Art in Cinema gained so much acclaim and popularity that attendance averaged around 500 per night and up to 800 per night at additional screenings at University of California, Berkley (MacDonald, 2010). This trend continued throughout most of the existence of Art in Cinema, additionally featuring numerous European award winners, old classics, and new works, all showcasing the assertive, exploratory choices that defined the genre (MacDonald, 2006).

His most controversial program series were his final two, series ten and eleven, which featured Hollywood films influenced by experimental techniques, accompanied by lectures from many of their directors or producers, including Cecil B. DeMille, Gene Kelly, and Joseph Mankiewicz. Stauffacher defended this decision saying: “these nine years of outstanding programs, no stringent policy has existed but that of being concerned with what is worth your [the Art in Cinema audience’s] interest in the film. True, our programs grew out of the avant-garde, but there is only so much avant-garde available” (MacDonald, 2006). This bold and alternative decision aside, Stauffacher’s understanding of the importance of an audience and their opinions is evident in his compiled program notes and collection of audience evaluations throughout the life of the program.

It should be noted that one major factor that sets Art in Cinema apart from many of its future successors is that it was a subscription-based program (MacDonald, 2006). This encouraged an audience committed to the series to continually return for each program, building upon the knowledge they had previously gained and experimenting with and expanding their cinematic preferences for avant-garde film. This also meant that his audience likely came from an upper and more educated class compared to someone who may buy a single ticket and attend for one night only. It more or less forced better commitment and engagement from the audience.

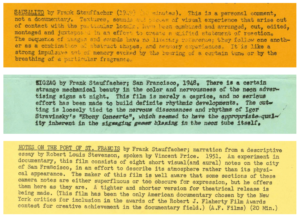

In order to encourage this engagement even further, Art in Cinema program notes were made available at each screening. Each one included a description of the films and often invaluable statements from the artists on their thoughts and intentions regarding the piece. Personal letters were written between Frank Stauffacher and experimental filmmakers such as Maya Deren, Luis Buñuel, Man Ray, and countless others, requesting statements and essays for his program notes regarding the specific works Stauffacher wanted to screen (MacDonald, 2006). Getting his hands on these films and notes was not always easy, and he occasionally had to alter his plans for any given series. Some older films were held by museums like the Museum of Modern Art, but many, especially the more recent ones, had never been a part of a traditional distribution pathway. To have not only their films to display but their thoughts and opinions accompanying them was considered invaluable and essential by Stauffacher for the Art in Cinema program.

At the end of each program, audiences were given evaluation forms to fill out, and from the four available collections of these audience evaluations, we can glean direct audience reactions to the films presented, as well as the series as a whole. The audience’s reaction to these films, notes, and occasional lectures was of the utmost importance to Stauffacher, and getting their feedback was essential to curating Art in Cinema. On each evaluation sheet, audience members were encouraged to select from a list of films of the entire series that they would like to see again, which ones they found “adequate,” and which ones they wished not to see again. Further, they were given space to leave “remarks” on the series, refer any friends to the program, and select their preferred weekend nights and times for future series. Aside from praise and positive comments, constructive remarks ranged from suggestions of themes for future series to calling the program notes too pretentious to which types of films felt out of place (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1946).

Frank Stauffacher carried his background in art studies and interest in cinema’s relation to other art forms into his approach to curating an experimental film exhibition. Using an artistic, educated committee and audience evaluations, he guided a more objective selection of films and thoughtfully gauged audience reactions and preferences. His program notes endeavored to enlighten and educate audience members, laying the groundwork for spectators and filmmakers to embrace the experimental form in future films. It took only one year from its creation for film enthusiasts like Amos Vogel to catch wind of the exceptional Art in Cinema program and reach out to Stauffacher for guidance on setting up a film society of his own in New York City with Cinema 16 (MacDonald, 2010). Frank Stauffacher and Art in Cinema began the zeitgeist of postwar experimental exhibition, and how we understand and consume avant-garde works today would not be the same without him.

Frank Stauffacher carried his background in art studies and interest in cinema’s relation to other art forms into his approach to curating an experimental film exhibition. Using an artistic, educated committee and audience evaluations, he guided a more objective selection of films and thoughtfully gauged audience reactions and preferences. His program notes endeavored to enlighten and educate audience members, laying the groundwork for spectators and filmmakers to embrace the experimental form in future films. It took only one year from its creation for film enthusiasts like Amos Vogel to catch wind of the exceptional Art in Cinema program and reach out to Stauffacher for guidance on setting up a film society of his own in New York City with Cinema 16 (MacDonald, 2010). Frank Stauffacher and Art in Cinema began the zeitgeist of postwar experimental exhibition, and how we understand and consume avant-garde works today would not be the same without him.

Ghetti, M. (n.d.) The Life and Art in Cinema of Barbara Stauffacher Solomon and Frank Stauffacher. BAMPFA. https://bampfa.org/page/life-and-art-cinema-barbara-stauffachersolomon-and-frank-stauffacher#fnref1

MacDonald, S. (2010). Cinema 16: Documents Toward History Of Film Society. Temple University Press.

MacDonald, S. (2006). Art in Cinema : Documents Toward a History of the Film Society. Temple University Press.

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. (1946). Audience Evaluations Film Series One, 1946. Art in Cinema collection, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, University of California, Berkley, CA United States.

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art & Stauffacher, F. (presumed). (1946). Film Series One Program Notes, Sep 27 to Nov 29, 1946. Art in Cinema collection, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, University of California, Berkley, CA United States.

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art & Stauffacher, F. (presumed). (1947). Film Series Two Program Notes, Apr 4 to May 2, 1947. Art in Cinema collection, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, University of California, Berkley, CA United States.

Stauffacher Solomon, B. (2005). Our Postwar Party. Zyzzyva 21(1).