by Wynn Kwiatkowski

Eloi, Eloi, lama sabachtani? [Mark XV:34].

There is no answer.

Merely the blank violence of the sun.

–The Thirst for Annihilation, Nick Land [1]

Hybrids are, or ought to be, sterile; and Kafka saw both himself and Red Peter as hybrids, as monstrous thinking devices mounted inexplicably on suffering animal bodies. The stare that we meet in all the surviving photographs of Kafka is a stare of pure surprise: surprise, astonishment, alarm. Of all men Kafka is the most insecure in his humanity. ‘This,’ he seems to say: ‘this is the image of God?’

-Elizabeth Costello, J.M. Coetzee [2]

Elephant[3] is about a school shooting. A brutal massacre is carried out by two culprits after the extensive following of the mundane and quotidian lives of various adolescents in a stereotypical early 2000’s high school. As a uniquely American phenomenon (and one that has only intensified in frequency as time has progressed), school shootings and the associated discourse by which they are surrounded are rife with emotional clichés and argumentative firestorms, more often openly antagonistic and discordant than contrapuntal, with various cacophonies of politicized opinions proffered on how to cope with the loss of life and how to prevent such actions in the future. Debates over probable causes still rage on today: Is it mental health? Perhaps gun control? Or maybe a lack of communal identity? The media attention the shooter subsequently receives? Psychiatric medications? The list of possible contributing factors goes on. But what is missing in these conversations is precisely the notion of excess, the remainder of “unemployed negativity,”[4] which is constitutive of school shootings that escapes totalizing systems of explanatory power created by reasonable inference. School shootings are exemplary sovereign events, bar none; in spite of a long list of possible causal factors, school shootings are reducible to no one single reason, or any combination of reasons thereof—for their reasons of occurrence are always in excess of reasons proffered. Or, to phrase this idea alternatively: there are no reasons to which school shootings can be totally reduced—school shootings happen because of an excess rage, of hatred, irreducible to: deteriorating mental health, chronic psychological disturbance, a traumatic childhood, etc. There are no “good” or “logical” reasons to give that perfectly account for why school shootings occur.

contributing factors goes on. But what is missing in these conversations is precisely the notion of excess, the remainder of “unemployed negativity,”[4] which is constitutive of school shootings that escapes totalizing systems of explanatory power created by reasonable inference. School shootings are exemplary sovereign events, bar none; in spite of a long list of possible causal factors, school shootings are reducible to no one single reason, or any combination of reasons thereof—for their reasons of occurrence are always in excess of reasons proffered. Or, to phrase this idea alternatively: there are no reasons to which school shootings can be totally reduced—school shootings happen because of an excess rage, of hatred, irreducible to: deteriorating mental health, chronic psychological disturbance, a traumatic childhood, etc. There are no “good” or “logical” reasons to give that perfectly account for why school shootings occur.

What makes Elephant so interesting as a cinematic thought experiment for tackling this issue is its portrayal of this uncontrollable sovereignty, as well as its lack of moralizing, its lack of unilateral authorial/directorial condemnation of the act of shooting up a school as such. The movie negatively enacts a refusal—a refusal of moral subjugation, of making Jared (the dark-haired shooter) and Eric (the blonde-haired shooter) absolutely, completely, wholly evil, whose acts of moral turpitude subject them to existence on an ethical plane lower than that of their victims. In fact, the film refuses any hierarchy of character, ordering of morals, or sense of finality that would be expected according to the logic of commonsensical thought and practice in the ethical representation of illegitimate, unprovoked, and immoral violence within cinematic art. What is most striking about the film is its pure refusal to preach, to condemn the act of massacring innocents at school clearly and unequivocally within the film itself. (And this the precise quality that made the film so controversial upon release: Elephant premiered just about four and a half years after Columbine, the American nation still reeling from and tending to its proverbial and literal wounds caused by its inaugural school shooting.)

A refusal to take a univocal textual stance on the (a)morality of school shootings and the film’s ethical portraits of the shooters being, at its best, apathetic, and, at its worst, sympathetic, challenge commonplace assumptions regarding narratives surrounding mass murderers. Due to its lack of unambiguous textual condemnation of the act of shooting up a school, it becomes all too easy for a morally dubious person to take inspiration to commit a school shooting from such a work of art, no doubt despite wishes of reception to the contrary. The film not having a clearly stated cinematic answer to the questions, Is this film going to inspire others to commit heinous acts against their peers? Should this film clearly condemn shooters as insane, malicious, and evil people? is what makes it so unnerving, so uncanny to watch, and it is precisely this quality that makes it such a fascinating case study in the role art should play from the standpoint of ethics and politics.

The film’s main assault is on the bullshit clichés and attitudes regarding The Assumption of the Throne of Moral Superiority upon which The Morally Righteous Person can sit, with which one could identify and subsequently experience all concomitant pleasures. Such positions of moral hierarchy are expurgated from the film’s ranks, at a level meta to the visible text. The film refuses to say, Of course school shootings are bad, of course there are plenty of people who suffer paranoia from such an event, of course the loss of innocent life is a tragedy, et cetera. The film is pure mimetic representation, a mimesis absenting in normative ethical claims regarding the content of what is represented on screen. There are no exemplars in Van Sant’s universe, there are no saviors, there are no masters—just a flat plane of immanence upon which each human finds him/herself trapped with no recourse for rescue. The two school shooters are treated with the same cinematic finesse as their unsuspecting victims: they are given equal screen time, equal investigation, equal fungibility. Furthermore, the psyches of the killers are not directly explored, nor are the respective psyches of the students; all characters are, in a sense, “flat.” Every single attribute about each character is given to the audience either through action, explicit dialogue, or facial/bodily expression. The movie lacks any internal soliloquizing about personal feelings, actions, or motivations, inculcating in the audience the feeling that we are watching a nature documentary, as if the students at this school were animals in the wild being stalked by predators.

By utilizing a real coldness and sterility inherent in the cinematographic choices, the camera operating as an impassive and unflinching recorder of the unfolding of this brutal scene, carefully documenting every step taken with its dispassionate gaze, frequently using long takes between cuts, Van Sant creates a documentary-esque effect. Lacking in quick cuts (with the notable exception of the planning scene), this style, the documentarian style, is achieved through its unnecessarily long shots and unusual emphasis on the background instead of foreground. The style is thoroughly “neo-realist,” the camera operating as an invisible “window on the world,”[5] a world which remains, to utilize a distinction theorized by Umberto Eco and applied to cinema by Thomas Elsaesser and Malte Hagener through the writings of Leo Braudy, diegetically “closed.”[6] According to such a conception of narrative each scene in Elephant operates according to the logic of an “invisible but omnipresent hand… elaborat[ing a] master plan,”[7] providentially culminating in the mass production of death. And this hand at work orchestrating such a massacre is also fundamentally, at its core, pleasurable to watch. As Baudry wrote: “Voyeurism is a characteristic visual device of the closed film, for it contains the proper mixture of freedom and compulsion: free to see something dangerous and forbidden, conscious that one wants to see and cannot look away. In closed films the audience is a victim, imposed on by the perfect coherence of the world on the screen.”[8] Victims indeed. Teetering the line between attraction and repulsion, Elephant’s portrayal of a school shooting is pleasurable yet revolting, titillating yet abject—the camera opening onto a barren wasteland of sovereign violence and death, silently watching an extermination, all for a perverse spectatorial jouissance, one equally as pleasurable to watch as it was for the killers to enact.

By utilizing a real coldness and sterility inherent in the cinematographic choices, the camera operating as an impassive and unflinching recorder of the unfolding of this brutal scene, carefully documenting every step taken with its dispassionate gaze, frequently using long takes between cuts, Van Sant creates a documentary-esque effect. Lacking in quick cuts (with the notable exception of the planning scene), this style, the documentarian style, is achieved through its unnecessarily long shots and unusual emphasis on the background instead of foreground. The style is thoroughly “neo-realist,” the camera operating as an invisible “window on the world,”[5] a world which remains, to utilize a distinction theorized by Umberto Eco and applied to cinema by Thomas Elsaesser and Malte Hagener through the writings of Leo Braudy, diegetically “closed.”[6] According to such a conception of narrative each scene in Elephant operates according to the logic of an “invisible but omnipresent hand… elaborat[ing a] master plan,”[7] providentially culminating in the mass production of death. And this hand at work orchestrating such a massacre is also fundamentally, at its core, pleasurable to watch. As Baudry wrote: “Voyeurism is a characteristic visual device of the closed film, for it contains the proper mixture of freedom and compulsion: free to see something dangerous and forbidden, conscious that one wants to see and cannot look away. In closed films the audience is a victim, imposed on by the perfect coherence of the world on the screen.”[8] Victims indeed. Teetering the line between attraction and repulsion, Elephant’s portrayal of a school shooting is pleasurable yet revolting, titillating yet abject—the camera opening onto a barren wasteland of sovereign violence and death, silently watching an extermination, all for a perverse spectatorial jouissance, one equally as pleasurable to watch as it was for the killers to enact.

The documentarian style’s particular application to the topic of school shootings forces an uncomfortable encounter with the violence constitutive of human-on-human decimation occurring because of… what? For what reason was the school’s population attacked, butchered, slaughtered? There is no real justification given for such a massacre to occur, besides a cursory scene of standard high school bullying in which Jared was the target. The shooting—instead of having a sympathetic backstory for the shooters, or a “good” or “logical” reason for occurring—simply happens; and it happens sovereignly, as each rapid fusillade of bullets expelled is sustained only by pure anger, rage, and indifference, each of which can serve no purpose beyond itself. And this is the precise excess that is irreducible to any totalizing justification: the fury, the rage, the apathy, the disregard for human life—all of which have no inhibiting factors, no rein with which one could subject it to control; for the violence inflicted by school shooters answers to no one.

The sovereign hatred imposed upon the students then becomes reducible only to mere randomness, aleatoricism, chance—which is to say, reducible to nothing, at least from the perspective of the rational power of the abstracted cogito. A certain chance confluence of factors engendered a massacre, one without sense, without meaning, without explanation. Chance, then, is pushed into the foreground as the constitutive element of the film. Indeed, one scene, an accidental encounter between three students, is shown from the perspective of each respective character, two of the them being friends, the third an outcast, illustrating that all the students at this high school are implicated in each other’s lives, and it is chance that is the ventriloquist, chance the puppetmaster, randomly choreographing events that would otherwise not occur. But chance is equally ferocious and deadly as it is fortuitous—chance is what causes the shooting, what orchestrates the performance ending with students dead. “Without horror and death or without the risk of them, where would the magic of chance be?”[9]

The sovereign hatred imposed upon the students then becomes reducible only to mere randomness, aleatoricism, chance—which is to say, reducible to nothing, at least from the perspective of the rational power of the abstracted cogito. A certain chance confluence of factors engendered a massacre, one without sense, without meaning, without explanation. Chance, then, is pushed into the foreground as the constitutive element of the film. Indeed, one scene, an accidental encounter between three students, is shown from the perspective of each respective character, two of the them being friends, the third an outcast, illustrating that all the students at this high school are implicated in each other’s lives, and it is chance that is the ventriloquist, chance the puppetmaster, randomly choreographing events that would otherwise not occur. But chance is equally ferocious and deadly as it is fortuitous—chance is what causes the shooting, what orchestrates the performance ending with students dead. “Without horror and death or without the risk of them, where would the magic of chance be?”[9]

Not only, however, is the salacious pleasure of seeing a chance outburst of crime followed by its identification, isolation, decontamination, and denouncement denied, but the audience is denied a wide array of possible pleasures standard in Hollywood films, from the comfort of classical narrative structure to identifiable archetypes of The Romance of the Lone Wolf Shooter or The Dynamic Duo Facing Off Against the World. In lieu of such puerile tropological fantasies is the equally puerile perversion of the children’s game “eeny-meeny-miny-mo,” recited by Jared before he kills his final two victims, completing his and his co-conspirator’s massacre. But immediately before: Jared kills Eric. (No honor among thieves.) Nor is there the possible perverse pleasure for the audience of a kind of nontransient, ‘til-death-do-us-part homosocial relationship between the two. But there is puerility, infantility, dissatisfaction; childish fantasies of grandiosity that never deliver, never satiating but ever tantalizing, fantasies that will not and can  not ever fulfill what we lack but will always instead lead to our own self-annihilation. Jared expresses little emotion during the shooting, and it should be noted that when the shooting starts, Jared seems bewildered, unsatisfied, as if his action of killing others couldn’t fulfill his fantasy of the selfsame act. To further compound the disillusionment is the failure of the rigged explosives to go off right before the shooting, in spite of grandiloquent plans to the contrary. The scene of the shooting is also lacking in both non-diegetic and diegetic music (two of Beethoven’s compositions, Moonlight Sonata and Für Elise, were present in select previous scenes, the former being non-diegetic, the latter diegetic), furthering the notion that such a scene held great romance in fantasy but of which it is in deficit when brought to fruition in reality. The literal act of shooting, translated from the realm of fantasy—in which there are no problems, no inhibitions, no setbacks—becomes underwhelming, aromantic, boring. Reality often disappoints, and the outcome of the shooting is less exciting, less attractive, than its fantasy, the killers murdering only a fraction of the personages of whose mass eradication they dreamt.

not ever fulfill what we lack but will always instead lead to our own self-annihilation. Jared expresses little emotion during the shooting, and it should be noted that when the shooting starts, Jared seems bewildered, unsatisfied, as if his action of killing others couldn’t fulfill his fantasy of the selfsame act. To further compound the disillusionment is the failure of the rigged explosives to go off right before the shooting, in spite of grandiloquent plans to the contrary. The scene of the shooting is also lacking in both non-diegetic and diegetic music (two of Beethoven’s compositions, Moonlight Sonata and Für Elise, were present in select previous scenes, the former being non-diegetic, the latter diegetic), furthering the notion that such a scene held great romance in fantasy but of which it is in deficit when brought to fruition in reality. The literal act of shooting, translated from the realm of fantasy—in which there are no problems, no inhibitions, no setbacks—becomes underwhelming, aromantic, boring. Reality often disappoints, and the outcome of the shooting is less exciting, less attractive, than its fantasy, the killers murdering only a fraction of the personages of whose mass eradication they dreamt.

At the end of the film there are no police storming the building, no final justice given to the students murdered—only a sick game played by Jared in which all possible paths toward life are foreclosed, all possible choices leading dreadfully to the same outcome: death. The game Jared plays is one of mere illusion—an illusion of mercy, of salvation. Van Sant renders the violence in, and infantile psychological nature of, school shooters, and offers no diegetic peace nor closure for the victims. He forces us to confront the violence of the world, the omnipresent brutality of humanity stalking us at all times, waiting to burst forth from the shadows of the unconscious. The coldness of the camera, the flatness of character, the senselessness of it all—there is no consolation proffered by Van Sant, no pat-on-the-back, no moral condemnation with which we could utilize to make ourselves feel better in order to inure us from the violence of the everyday and the exceptional.

✟✟✟

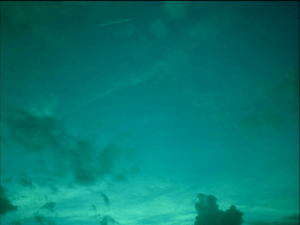

Nietzsche once remarked that the human was an animal bred to remember promises,[10] conscious only through the biological inscription of pain.[11] Emphasis on animal and pain. Nature is then, for Van Sant, the ultimate reckoner, the god that envelops us, totally crushing, totally agonizing, completely inhospitable, and inflicting of tremendous tribulation upon us without a shred of remorse. Thus the final shot of Elephant shows the clouds, signifying to the audience the impersonality of nature, of God, of anything else toward the suffering, evil, and pain experienced (and caused) by the animal bred to remember promises. This is the final image with which we are left: the clouds in the sky, beautiful, floating along, without respect to the circumstances of our species; time passing, stoically, patiently, rhythmically. And, of course, we sit with the associated affects such an image generates: utter isolation, utter non-redemption, utter meaninglessness—all of which are situated at the center, and circumference, of life.

remorse. Thus the final shot of Elephant shows the clouds, signifying to the audience the impersonality of nature, of God, of anything else toward the suffering, evil, and pain experienced (and caused) by the animal bred to remember promises. This is the final image with which we are left: the clouds in the sky, beautiful, floating along, without respect to the circumstances of our species; time passing, stoically, patiently, rhythmically. And, of course, we sit with the associated affects such an image generates: utter isolation, utter non-redemption, utter meaninglessness—all of which are situated at the center, and circumference, of life.

And yet, in spite of the tumultuous chaos in which we are thrust at birth that lasts until our death, art is still made. All art, by definition, being an abstraction from the profane circulation of medium-specific “raw materials” (i.e., language, physical objects, visual scenes, un/harmonious noise, etc.) with which an artist works, thus obtains a salvific and sacred significance, proliferating in meaning, drawing us into self-introspection, offering us a sense of redemption from the meaninglessness and distractions so constitutive of human life.[12] “Fiction,” David Foster Wallace once said pithily, “is about what it is to be a fucking human.”[13]—a statement made that is equally applicable to other media in which artistic aspirations are present. Art is for exploring our humanity. And to be human is paradoxical: to be a self-aware animal, a monstrous thinking device mounted inexplicably on a suffering animal body, an animal wrenched out of nature, and an animal, at that, condemned to a search, a never-ending search, for what will always be unattainable, always just outside our grasp—the total and complete possession of absolute and unqualified meaning.

[1] Land 2003, p. 77.

[2] Coetzee 2004, p. 75.

[3] Van Sant 2003.

[4] Bataille 1997, p. 296.

[5] Elsaesser and Hagener 2015, p. 14.

[6] See Ibid, pp. 17-19, for a discussion of the realist/constructivist divide in early film theory and practice. While the meanings of the terms “realist” and “constructivist” are fairly easy to understand when applied to film form, their respective related semantic correlates, the closed/open film, are less obvious. Elsaesser and Hagener quote Leo Braudy in discussing the difference between an closed versus open filmic world: “The difference [between closed and open films] may be the difference between finding a world and creating one: the difference between using the pre-existing materials of reality and organizing these materials into a totally formed vision; the difference between an effort to discover the orders independent of the watcher and to discover those orders the watcher creates by his act of seeing.” Elephant is, in my opinion, closed—although an argument could be made for it being open as well.

[7] Ibid, pp. 17-18.

[8] Quoted in Ibid, p. 18.

[9] Bataille 1997, p. 46.

[10] Nietzsche 2000, p. 493.

[11] See Botting and Wilson 2001, pp. 111-113, for a reading of Nietzsche’s On the Genealogy of Morals in which the two authors contend that, for Nietzsche, it was out of the infliction of pain and its collective remembrance by the human body that consciousness emerged in the homo sapiens.

[12] The notion of art having a soteriological significance is at work in Elephant itself, as, at the beginning of the shooting, the photography student Elias takes a picture of Jared and Eric, and it is presumably because of this photo that Elias was spared.

[13] McCaffery 2013.

——————————————————————-

Bataille, Georges. The Bataille Reader. Edited by Fred Botting and Scott Wilson. Oxford: Blackwell, 1997.

Botting, Fred, and Scott Wilson. Bataille. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave, 2001.

Coetzee, J. M. Elizabeth Costello. New York: Penguin Books, 2004.

Elsaesser, Thomas, and Malte Hagener. Film Theory: An Introduction Through the Senses. Routledge, 2015.

Land, Nick. The Thirst for Annihilation: Georges Bataille and Virulent Nihilism: An essay in atheistic religion. London: Routledge, 2003.

McCaffery, Larry. “A Conversation with David Foster Wallace by Larry McCaffery.” Dalkey Archive Press, August 2, 2013. https://www.dalkeyarchive.com/2013/08/02/a-conversation-with- david-foster-wallace-by-larry-mccaffery/.

Nietzsche, Friedrich Wilhelm. Basic Writings of Nietzsche. Translated by Walter Kaufmann. New York: Modern Library, 2000.

Van Sant, Gus. Elephant. HBO Films, 2003.