Notable film reviews from 2023, written by UNG alumni, students, and faculty.

All of Us Strangers (Andrew Haigh)

“I’ll protect you from the hooded claw. Keep the vampires from your door,” says Adam, a character played by Irish actor Andrew Scott in Andrew Haigh’s 2023 film All of Us Strangers. The line of dialogue, which recalls lyrics from the song “The Power of Love” by British pop group Frankie Goes to Hollywood, perfectly encapsulates the tensions between grief and love experienced by many who identify as a part of the LGBTQ+ community. All of Us Strangers masterfully balances these profound emotions through a unique take on a ghost story that explores sexual identity, familial relations, love, and loss.

The film follows Adam, a secluded writer, who one night meets his apartment neighbor, Harry, played by indie-darling Paul Mescal. The pair begin an intimate and tender relationship built on a mutual understanding and appreciation for the other. Between scenes demonstrating Adam and Harry’s relationship flourishing, Haigh constructs a parallel narrative in which Adam visits his family home. Here is where the ghost story begins. Adam takes several trips to his childhood home throughout the film. While in the house, Adam has visions and interactions with his parents (played by Jamie Bell and Claire Foy), whom Haigh explicitly tells us died in a car accident when Adam was a child.

The film oscillates between the two locations and the two sets of relations: the apartment, where Harry and Adam spend their time, and Adam’s childhood home, where Adam converses with his mother and father. Haigh’s skilled use of narrative, emotionally-driven dialogue, and well-constructed characters result in a compelling meditation on love and its application in many spheres: family, romance, neighbor, and self.

While 2023 saw its share of big movies that made a splash in public discourse, such as Barbie, Oppenheimer, and Saltburn. All of Us Strangers diverges from the status quo as a small but mighty independent film that packs an emotional punch and leaves its viewers in a state of wonderment.

Chloe Kwiatkowski

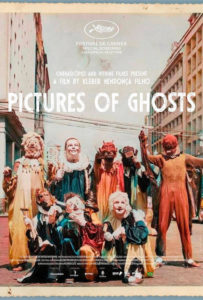

Pictures of Ghosts (Kleber Mendonça Filho)

In this poetic essay film, director Kleber Mendonça Filho sets off on a ghost hunt through his hometown of Recife, Brazil. Many of the city’s charming movie palaces once so beloved by Filho in his youth, are now closed—reduced in the present day to abandoned shopping centres, churches, and office buildings. Pictures of Ghosts is an elegy dedicated to these dilapidated landmarks, as Filho nostalgically reflects on his adolescence, film-going galivants, and his early filmmaking career—all chapters in Filho’s life deeply indebted to Recife and its cinemas. The film’s images are also not confined to the now hollow lots, but the director, using archive footage and film clips, interweaves poignant moments from the history of the city into the film. This mode of montage accompanied by Filho’s wistful voiceover, brings Recife’s past and its cinemas back to life once more. (Ghosts, after all, are very much at home in celluloid.)

The Brazilian auteur, never allowing the film to teeter into overly sentimental revery, takes off his rose-coloured glasses from time to time to confront issues such as the gentrification of the city and the more secret, dark histories of Recife (one sub plot involves the Recife theatre, Art Palácio, which had begun its life as a Nazi-backed project.) My favorite thematic subtlety is the feeling conjured by the collision of the ephemerality of the archive footage with the physical spaces of the cinemas and Recife’s downtown. This juxtaposition strikes a perfect note of nostalgia and sadness, as if along with the eviction of the physical cinemas, the Recife citizens captured in the footage and the milieu they once occupied are also slipping away.

While the “love letters to cinema” genre (The Fabelmans, Babylon) has been oversaturated to the point that the label can only induce groans at this point, Filho wisely sidesteps such accusations with a timely message. The cinemas of the world may too soon only exist as the faded memories of sentimental filmmakers and cineastes.

Kyle Brandys

Bottoms (Emma Seligman)

After decades of films like American Pie (1999), Revenge of the Nerds (1984), and Animal House (1978), straight, white men have had really a lot of representation in the field of morally dubious sex comedy. Male dominance in film has been challenged several times with films spanning the genres of crime, sci fi, and drama, but this niche-yet-powerful genre has remained unchallenged, unchanged. Some might see this as an acceptable compromise in the gender wars. I personally see it as a loss.

A loss that the lesbians have finally started to push back on.

Lesbian media has a particular reputation for being sad and drawn out due to a history dating back to pulp novels and the Hays code; but those limitations keep media about and for queer women largely inaccessible. Bottoms begins to challenge that. Focusing on not only queer women, but queer women who are neither saints nor tragic, allows for humor and levity that lesbian media sorely needs. The dynamic duo of PJ (Rachel Sennot) and Josie (Ayo Edebiri) provide the audience with a version of queer women with interesting and compelling faults that allow for characterization that feels relatable and relevant. They want what every teen lesbian wants – connection, affection, sex with a really hot girl –, and they might just do something less than great to that end. The feeling of watching their stupid, but deeply relatable, decisions turn into complex consequences felt far more like my life than any dramatic period piece where one or both of the women die in the end.

Letting people be bad, letting queer women be bad, lets us all have a deeper connection to our own narratives on the screen. Diverse stories are better stories when they get to show parts of life that are less than presentable, less than perfect, a little messy.

Robin Turner

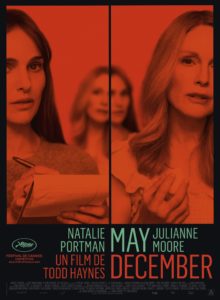

May December (Todd Haynes)

Surely what will be a revered classic years from now, May December is a delightfully layered film about the excavation of truth in both cinema and everyday life. Todd Haynes, the modern master behind Carol, I’m Not There, Poison and more, crafts a chilling and darkly humorous piece that never fully answers its questions about power. Haynes proudly riffs off of Bergman’s Persona and has talked about this at length. It may seem early, but it feels apt to say that Natalie Portman and Julianne Moore’s duo of a dedicated actress and the woman she’s playing in an upcoming film is a truly generational pairing.

Portman displays immense levels of nuance with her performance, and this performance enhances an already phenomenal script by now-Oscar-winner Samy Burch. Portman’s Elizabeth Berry is an actress trying to connect with Gracie Atherton-Yoo (Moore), a woman who went to prison for having an affair with a seventh-grader in the early 1990s, a boy that she eventually married (Charles Melton). Elizabeth is the audience’s “in” to the story and the lives of two controversial people, but she is not some guiltless or objective observer. Her interference in the Atherton-Yoos’ lives for art’s sake completely disrupts the family’s (relatively) quiet life. She is not corrupted by her exposure to the manipulative, subtly malignant presence of Gracie, but she recognizes that in herself which is similar to Gracie, and tries to deny it. It is that which truly reveals what the film is aiming to evoke in its viewers: the effects of creatives mixing subjectivity with externality.

Of course, discussion about May December would be incomplete without mention of Charles Melton’s once-in-a-lifetime performance. He perfectly captures the stunted maturity and physicality of a man who was groomed as a child and never questioned that relationship. Melton’s character is in his mid-thirties yet has the body language of a much younger man. His portrayal of domestic obedience and stagnation is one of the most compelling performances this century. He is ultimately the emotional center of the film and elevates the film beyond the already groundbreaking work by Portman and Moore. Todd Haynes has created a must-see cinematic wonder that should be mentioned among the greats, until he manages to make something even better.

Chayce Ward

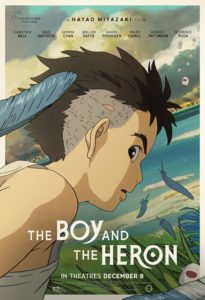

The Boy and the Heron (Hayao Miyazaki)

After 12 years since his previous film, Hayao Miyazaki comes back with what many people consider his final film (even though we all know Miyazaki will never retire for good), The Boy and the Heron. The film follows young Mahito Maki as he navigates how to live after his mother’s death, moves to a new town, and gets a stepmother. As soon as he arrives, he is tormented by a Grey Heron until he is eventually sucked up into a new world where he meets an ensemble. It seems like a big plot but it’s nicely divided into two sections, each with their own distinct tone. The first is a more grounded and gritty horror-like plot as the Grey Heron continuously goes after Maki. The second is more reminiscent of a typical Miyazaki film but only in image; the story and tone mirror the deeper themes of the first half.

The title “The Boy and The Heron” was used for western audiences rather than the original Japanese title, “How Do You Live?” The original title makes more sense since the book How Do You Live? plays a role in the film. Ghibli changed it since they thought “The Boy and The Heron” would sell more than the alternative. While the new title does work, the original identifies one of the core themes that the film struggles with. While this film may not be Miyazaki’s final film (even though he is 88 years old), it is very much reminiscent of Akira Kurosawa’s Dreams (1990). It is a very self-reflective movie that mirrors Miyazaki’s own relationship with his son, as well as themes of accepting death, the end of one’s legacy, and what will happen to that legacy once that person is gone. The film’s mood compliments these themes very nicely.

As I mentioned earlier, this very much feels like a Miyazaki film (think Spirited Away (2002)) in how its world is presented, but that undertone of cheeriness that most of his films have is replaced by an undertone of worry and grit. Whether this is Miyazaki’s final film or not, I encourage everyone to watch it at least one time as the themes and ideas of the film are core to what every human being is: how do you live?

Jordan Darnell

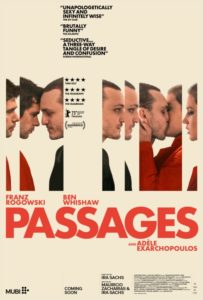

Passages (Ira Sachs)

It’s no surprise that a little film like Ira Sach’s Passages floated under the radar for most of the awards circuit this year. On one hand, the film appears to be one-note, defined by its sexual intrigue: a married filmmaker cheats on his husband with a woman. The MPAA originally slapped the film with a hard-to-market NC-17, a commercial death warrant in the United States. Additionally, the plot seems almost too simple and cliché: a love triangle about a philandering film director? But the filmmaking purposefully follows an easy design (even down to its primary-color-heavy palette by production designer Pascale Consigny) to subvert its audience’s expectations. Sach’s characters lead surprisingly nuanced lives that appear simultaneously progressive and traditional — and keep the audience guessing at their motivations and next actions.

The film’s international cast, featuring Franz Rogowski as Tomas, Ben Whishaw as Martin, and Adèle Exarchopoulos as Agathe, play off each other like magnets, sometimes attracting each other, sometimes repelling. Tomas, the filmmaker, seems plagued by his impulsivity from the first scene to the last, but the audience is not asked to board his emotional rollercoaster; instead, because the film is shot in such an expert, simple, static fashion, viewers are allowed to sit back as removed spectators of the actors’ grounded, believable performances. The camera often lingers on conversation, moments of intimacy, or an actor doing nothing other than listening — and when a director can communicate undefinable ideas about relationships by letting their audience observe heartbreak without dialogue, isn’t this a definition of cinema?

And while the film’s main character could be defined as bisexual (but isn’t during its taut 91 minutes), the filmmakers choose to sidestep labels and politics, again seemingly to keep it simple and focused on the unexpected actions and interior lives of its three main players. In a landscape of big-budget Hollywood fare and indie movies urging their audiences to think politically, Passages stands out as a refreshing return to “less is more” filmmaking.

As an added note, the film is a must-watch for any fan of statement-piece sweaters, of which there are many.

James Mackenzie

Beau Is Afraid (Ari Aster)

Ari Aster’s Beau is Afraid isn’t a horror movie, but it is plenty scary and agonizing. In the wake of Covid lockdowns and shelter-in-place directives, I’ve noticed more people react to films in terms of intensity; a controllable panic attack. Regardless, it’s promising that there are still opportunities for unique films like Beau to be given proper funding and distribution (courtesy of A24).

Beau (Joaquin Phoenix) is a neurotic, reclusive man who has never once felt comfort in his life. When he receives news of his domineering mother’s passing, Beau musters up the gumption to escape his apartment on a quest to get home for the funeral. Along the way, he navigates a living nightmare of surrogate overbearing parents (as if one wasn’t enough), played by Nathan Lane and Amy Ryan, and a Gilliam-esque troupe of theater performers living in the woods.

The film plays out with a sort of dream logic that remains thematically focused on one thing: every choice Beau makes seemingly brings pain to himself and the people around him. After Hereditary and Midsommar, Aster remains preoccupied with the anxiety of being around family, maybe because they’re the hardest people to lie to. The filmmakers exquisitely depict a world that is simultaneously obsessed with and uncaring about Beau – the reflection of a lifelong guilty conscience, orchestrated by the hand of mother Mona (Patti LuPone in the present, Zoe Lister-Jones in the flashbacks).

Near the end of the film, there’s a startling scene in an attic that made me think, “A) I love that this moment is in a wide release US movie, and B) what are we supposed to get out of this?” Although Beau is Afraid is compelling and memorable, it’s puzzling as to what motivates Aster to deliver this specific type of uncomfortable experience. I’m not sure what constitutes Cringe Cinema but Beau offers viewers an outlet to squirm and mutter, “That’s messed up.”

Andrew Salerno

Past Lives (Celine Song)

In the opening frame of Celine Song’s film Past Lives (2023), we observe an Asian man and woman sitting at a bar with a white American man. Subtly, the camera pushes in. Unseen bystanders begin to narrate, trying to guess the relationship dynamic between the three. Like the narrators, we – the audience – are slowly being drawn into their world, relying upon slight facial expressions and reading of lips to reveal truth. The camera continues to push in with the two male characters, Arthur and Hae Sung, falling away, leaving us to focus on the woman, Nora. The narrators are perplexed with one stating outright, “I have no idea.” As Nora’s gaze deepens, so does our understanding of this film. The truth, like our lives, is messy and complicated, and not easily interpreted. Nora continues looking into the eyes of Hae Sung before turning away to meet the camera, directly breaking the fourth wall. We’ve been caught. The film abruptly transitions to “24 YEARS EARLIER.”

We are taken through their lives, meeting 12-year-old Na Young and Hae Sung first as classmates in Seoul, South Korea and again in their mid-twenties as they build their lives worlds apart. Na, now Nora, emigrated with her parents leaving behind Hae Sung and the only culture she had ever known. Throughout the film, Song’s staging is steady and intentional. With a background in theatre, she brings an efficient understanding of spatial relationship to the medium. Her framing is complimented by proficient, yet profound dialogue, that often hits like a punch in the heart. Song cuts deep in what appears to be the mundane. The story takes its time to unfold, with tension building up to the third act when Hae Sung finally visits Nora in New York. By now, Nora is an accomplished playwright married to fellow writer Arthur. In coming face-to-face with her childhood sweetheart, she must confront a past version of herself and let go of a life that could have been.

Past Lives is not a standard love triangle, but rather exists in shades of gray. The film belongs in a category with other recently released highly personalized, often autobiographical films such as Aftersun (2022) and All of Us Strangers (2023). Like many of us, the filmmakers seem to be searching for a sense of self and identity in the post-pandemic, politically polarizing world in which we live.

Robyn Hicks

The Zone of Interest (Jonathan Glazer)

Jonathan Glazer’s first feature film in nine years proceeds from a daring enough narrative conceit – a depiction of life at the Auschwitz death camp, only as experienced from the other side of its walls. We follow the family of commandant Rudolph Höss as they navigate their day-to-day lives, our knowledge of what’s transpiring mere yards away keeping us ever aware of the sickening context within which the quotidian events we’re witnessing are unfolding.

What truly sets the film apart, however, are the formal strategies Glazer and his team employ. Utilizing a multi-camera set-up within the Höss residence and operating from a remote hub, DP Lukas Zhal films the action from a completely dispassionate perspective, utilizing natural lighting and allowing the actors to simply exist in character rather than feel as if they are performing. Dramatizing the normalcy of the Höss family’s lives in this way, without any of the psychological or emotional underlining of traditional narrative film form, holds us at a distance even while the stomach-churning sound design by Tarn Willers and Johnnie Burn keeps the adjoining camp’s horrors immediate through their continuous presence on the soundtrack – we never see any of the atrocities within, but we constantly hear the barking of dogs, the shouting of guards, the report of gunfire, and the churning mechanical drone of industrialized murder throughout the film.

The seemingly impossible tonal balance of confronting us with the banal humanity of this family while also never letting us forget what monsters they are is where the film’s true resonance lies. When we talk about humanity, we like to frame it within the more beneficent aspects of our collective character; what this film confronts us with is the understanding that we have to reckon with the darker side as well, because to think of evil as something other, or as something inhuman, is to deny its roots and thus allow it to continue in perpetuity. We may not be as bad as them, but they are just as human as us, whether we want to face that truth or whether we would prefer that it fade to a dim background noise.

Christopher Sailor

Perfect Days (Wim Wenders)

Perfect Days was first imagined as a documentary project about the 17 public toilets across Tokyo which were designed and implemented for the 2021 Olympic Games. Since the Games were disrupted and postponed (then postponed again), Wenders was brought in to honor them on film. The transformation of this project to fiction narrative does not erase this documentary impulse. In fact, we spend so much time in the film quietly roaming around Tokyo streets and public spaces that we may as well be watching B-roll for the abandoned project. Like Wenders’ previous documentary works on Japan, such as Tokyo-Ga (1985), the camera in Perfect Days lingers on quirky people, naturalizing their behaviors through duration. And it consistently returns to low-angle shots of Tokyo Tower looming above the city like a guardian angel.

In many ways, Perfect Days is a culmination of Wenders’ oeuvre. It is born of documentary impulses. It is a road movie. It admires artists of many mediums. It features Lou Reed. It is a meditation on living a meaningful life. And it brings to the foreground a quiet, unassuming character. The protagonist Hirayama (played masterfully by Koji Yakusho) is in some ways a familiar character: he is solitary, thrives on routine, and values work ethic. But Wenders and co-writer Takuma Takasaki refuse to turn Hirayama into a cliché. Though he is generally solitary, Hirayama’s life is shown to be equally as fruitful with people suddenly thrust into it, whether that be a co-worker’s girlfriend, a niece running away from home, or a stubborn stranger on a park bench. Though he is regimented and is shown to follow the same exact routine day by day, Hirayama’s artistic inner life as a photographer is rich, as evidenced by his dream sequences – feverish black-and-white experimental films that evoke Maya Deren’s psychological filmscapes. Hirayama is not a curmudgeon who is “set in his ways”, but rather an artist who has been set free from modern expectations of success. He cleans public toilets for a living, but his work ethic seems to be just as much about honoring the majesty of these public art pieces as it is about cleanliness.

Through their protagonist, Wenders and Takasaki fold together the art of music (the film has an impressive 1970s mostly-diegetic soundtrack), with the art of architecture, with the literary arts, with graphic arts. This gentle meditation on living a meaningful, artistic life is shockingly unassuming as it honors the most ordinary and majestic spaces that bring community together.

Yelizaveta Moss