The sociolinguistic features of the Japanese language carry different implications to their counterparts in other languages, and are interpreted by Japanese audiences in different ways. The unique social, cultural, and contextual qualities that make up the Japanese language allow for native audiences to interpret authorial intent and specific details about a story and its characters simply through the way the characters speak. In this paper, regional dialect, formality, and gendered language/pronoun usage are discussed and their usage in media analyzed, which are then applied to different entries in the Yakuza video game series to provide examples and show their significance to audience interpretation. The findings show many of the different details about character, society, and culture that Japanese media are able to portray through speech styles alone, how the native audience is able to clearly interpret them, and why it is important for this discussion to be encouraged in foreign scholarly discussion.

Dialect

Attribution of traits

While the concept is not exclusive to any one language, Japanese dialects play an important role in establishing significance not through what is said, but how it is said. Rahardjo writes that people are typically classified based on the way they speak, and that there are some who believe that linguistic differences serve as one of the most reliable indications of social position and character (Rahardjo 6). There are many different dialects in Japan, all of which retain different social and cultural implications. However, as it is one of the largest and most represented dialects in Japanese media, I’ve chosen to focus primarily on the Kansai dialect, specifically the variant spoken in the Osaka region, and its influences and implications. Prior to the 1980s, the dialect was regularly regarded as a rougher and more harsh way of speaking when compared to Standard Japanese (SturtzSreetharan 431). However, eventually, associations of laughter and fun became more common, shifting perception in a positive direction. For the majority of Japanese viewers, Kansai dialect calls to mind specific stereotypes that differentiate it from other ways of speaking. Some of the features associated with Kansai dialect include honesty, passion, loudness, and a good spirited or silly personality (Rahardjo 9). One reason for the dialect’s rougher perception is that, alongside its tone, many words frequently used in both formal and informal speech in the Kansai region are the same as or similar to typical masculine or informal words in Standard Japanese, such as the use of ‘chau’ over ‘chigau’, meaning “to differ.” In works of fiction, adhering to specific linguistic features can occasionally help audiences understand and empathize with characters easier. Many believe that linguistic stereotypes can serve as energy saving devices to assist with recognizing the differences between groups of people (Rahardjo 7). In other ways, Kansai dialect is strongly associated with comedy, largely in part to the manzai comedy acts the region is known for (SturtzSreetharan 432). This fast-paced style of comedy consists of a “fool” and a “wit” bouncing off of each other while discussing different everyday events or situations. These two personalities work together towards the successful construction of manzai, and can’t function without the other. Manzai comedy acts are still enjoyed by audiences today in various forms, such as the popular comedy group Gaki no Tsukai. The persistent popularity of this style of comedy allows for easy recognition in audiences as it continues to be reused in Japanese media today.

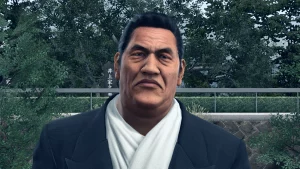

Within the Yakuza series, there are many different examples of dialect, particularly Kansai-ben, applying traits to a character or group of characters. While the prequel game Yakuza 0 sets half of its story in Osaka, the earliest chronological instance of a group whose perception is influenced in part by their dialogue is the introduction of the Omi Alliance in Yakuza 2 and its remake Yakuza Kiwami 2. The Omi Alliance is an organization based in the Kansai region, and the only other group to rival the Tojo Clan in size. Efforts are made by Tojo leadership to push for peace between the two groups, but a coup by most of the Omi’s officers prevents those plans from coming to fruition. Many identifiable traits of Kansai speakers become apparent as soon as the second major cutscene in the game, when Terada, chairman of the Tojo and formerly a member of the Omi, is shot dead by Omi assassins during a meeting with Kiryu at his father’s grave. Their actions are brutal and quick, and especially aggressive given that they take place at a graveyard, which exaggerates the assertive Kansai image. The thugs’ threats to Kiryu are conveyed in casual, impolite speech, made to sound even more so given Kansai dialect’s perceived rough tone. Later, when Kiryu is successfully able to land a meeting with Omi Alliance leadership, more of these traits are shown. The majority of the officers are openly antagonistic to Kiryu, using belittling language and taunting him with his relationship to Terada. The chairman of the Omi, however, embodies other Kansai features, as he is rather forward with Kiryu and passionate about his desire for peace between the two groups until he is forcibly taken away. Another faction in the same game that embodies Kansai traits is the Osaka Police Department, specifically through the deuteragonist Kaoru Sayama. As lead detective, Kaoru’s use of Kansai dialect and general demeanor gives her an assertive, rough tone while still maintaining professionalism with her peers. Her conversations with her boss have an air of familiarity to them, and she takes a far more imposing tone with those she is at odds with. The characters in these two groups embody different traits, all of which are often recognized by Japanese audiences as features of Kansai, and their language makes their roles clearly stand out against the rest of the Standard Japanese speaking cast.

In regards to manzai depictions of comedy, special mention goes to recurring character Goro Majima, one of the most recognizable characters in the series. Majima’s appearance is equal parts outlandish and imposing, and his actions regularly unsettle those around him. Much of Majima’s interpretation comes from his allusions to manzai comedy in that he regularly plays the role of the ‘boke’, or ‘fool’, to the unsettlement of those around him. Throughout the game, Majima either winds up in or creates ridiculous scenarios, which usually results in Kiryu reluctantly playing the ‘tsukkomi’, or the straight man.  For example, in Yakuza Kiwami, if the player chooses to go bowling, there’s a chance Majima will appear dancing behind Kiryu, taunt him on his bowling abilities, and challenge him to a match. His thick, exaggerated Kansai accent causes him to stand out, even amongst other Kansai speakers, and gives him an easily recognizable comedic energy. However, Majima is also one of the most violent characters in the game, and often switches from humor to anger at the slightest offense. In another scene in Yakuza Kiwami, Majima nearly beats a man to death with a baseball bat for not laughing alongside him, which shocks all present. This results in Majima having a rather contradictory presentation, mixing comedy with cruelty, and it works as well as it does because Japanese audiences are able to quickly identify his character as soon as his first spoken line.

For example, in Yakuza Kiwami, if the player chooses to go bowling, there’s a chance Majima will appear dancing behind Kiryu, taunt him on his bowling abilities, and challenge him to a match. His thick, exaggerated Kansai accent causes him to stand out, even amongst other Kansai speakers, and gives him an easily recognizable comedic energy. However, Majima is also one of the most violent characters in the game, and often switches from humor to anger at the slightest offense. In another scene in Yakuza Kiwami, Majima nearly beats a man to death with a baseball bat for not laughing alongside him, which shocks all present. This results in Majima having a rather contradictory presentation, mixing comedy with cruelty, and it works as well as it does because Japanese audiences are able to quickly identify his character as soon as his first spoken line.

Juxtaposition Against Standard Japanese

One of the more interesting elements of dialect is how it compares and attributes traits to speakers of Standard Japanese. Standard Japanese, or ‘hyōjungo’, is typically referred to as the ‘common language’ of Japan, and as such, is considered standard and does not necessarily have any special features associated with it like a regional dialect does. However, in stories where dialect speaking characters are also prominent, significant traits can often be seen through juxtaposition. One of the reasons why a language may be standardized is to codify and increase uniformity of the norm, and to serve as a model to a larger speech community (Twine 430). Over time, in the name of national pride, the modernization and standardization of the Japanese language factored into the growth of national unity and identity (Twine 432). This focus on homogeneity and hierarchy reveals a concern over maintaining harmony, consensus, and interdependence within Japanese society and culture (Matsumoto and Okamoto 28). As such, uniformity and group-orientedness can be seen as traits of the Standard Language. When a character (or group of characters) speaks Standard Japanese and is paired alongside another character or group that speaks a regional dialect, the former can occasionally be seen as representative of typical Japanese traits or ideologies, or as a representative of Japanese national identity. As such, any deviations from this norm made by either speaker stand out, and say something about the character in question.

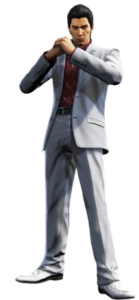

In Yakuza, Kiryu can be seen as an exaggeration of the ideal ‘masculine’ Japanese male. Despite his rugged appearance, he typically tries to conform to society by keeping to himself, completing tasks without complaint, and a general consideration for his fellow man. At the same time, however, he is true to his desires, and cannot abide injustice, regularly defending himself, protecting innocents, and standing up to his superiors. In a research article over “gendered modernity” in Japanese media, Occhi notes that “heroes, classically, speak hyōjungo Standard Japanese”, which has led to heroes like Kiryu speaking “normally” (Occhi et al 412). Majima, on the other hand, is passionate and expressive. During interactions between these two characters, the juxtaposition results in Kiryu’s more traditional traits, such as his stoicism and neutral demeanor, standing out. Where Kiryu conforms to societal norms works together with his deviations from it and Majima’s contrasting elements to reinforce his image as a Japanese man who fits into society while doing the things most wish they could. The conflict between the Tojo clan and the Omi Alliance can also be looked at through a different lens thanks to their spoken languages. The Tojo are based in Tokyo, and all speak the standard language. The Omi are centered in Osaka, and speak Kansai-ben as a result. In their conflict in Yakuza 2, the Tojo attempt to keep things traditional through actions like trying to reinstate the patriarch’s bloodline to lead them and vying for peace with the Omi, sending Kiryu to act in an official capacity. The Omi, conversely, are significantly more aggressive in their conduct, trying to break the status quo through a violent coup and interfering during unexpected moments like a funeral. On a larger scale, their conflict can be seen as a battle between ideologies, with the Tojo representing the traditional national identity and the Omi acting as agents of violent change.

There are also instances in the series of characters dropping their accents in favor of taking on the image associated with Standard Japanese speakers. In Yakuza and its remake Yakuza Kiwami, the character Yukio Terada is introduced as a former Omi Alliance member currently working with the Tojo.  As a member of an organization based in the Kansai region, it would be expected of him to adhere to some of the traits associated with Kansai people and to speak with a dialect. However, he embodies neither of these features, speaking in Standard Japanese and presenting himself in a very neutral way. Kiryu remarks after meeting him that he’s unsure of his motivations, part of which can be owed to his seemingly contradictory presentation to what one would expect. In the following game, Yakuza 2 and Yakuza Kiwami 2, Terada is murdered very early on, but flashback scenes to his actions before his death suggest that he may be intentionally using Standard Japanese as an additional component of crafting a persona that fits in better with his position as chairman of a Tokyo based organization. Also in the second game, Kaoru Sayama noticeably drops her Kansai accent during the segments of the game that take place in Tokyo. Despite her character having been previously established as tough and unconcerned with what others think of her, this decision suggests that there still appears to be a desire to conform in order to maintain professionalism while on the job. However, in a later scene where she and Kiryu take a break together in the city, she lets her guard down and her accent comes back, along with a much more casual attitude. The act of using Standard Japanese in order to conform reinforces the conformist element of the language, and these scenes imply that while Kaoru embodies the open and assertive image typically associated with Kansai people, there is still an element to her that wishes to avoid unnecessarily going against the grain.

As a member of an organization based in the Kansai region, it would be expected of him to adhere to some of the traits associated with Kansai people and to speak with a dialect. However, he embodies neither of these features, speaking in Standard Japanese and presenting himself in a very neutral way. Kiryu remarks after meeting him that he’s unsure of his motivations, part of which can be owed to his seemingly contradictory presentation to what one would expect. In the following game, Yakuza 2 and Yakuza Kiwami 2, Terada is murdered very early on, but flashback scenes to his actions before his death suggest that he may be intentionally using Standard Japanese as an additional component of crafting a persona that fits in better with his position as chairman of a Tokyo based organization. Also in the second game, Kaoru Sayama noticeably drops her Kansai accent during the segments of the game that take place in Tokyo. Despite her character having been previously established as tough and unconcerned with what others think of her, this decision suggests that there still appears to be a desire to conform in order to maintain professionalism while on the job. However, in a later scene where she and Kiryu take a break together in the city, she lets her guard down and her accent comes back, along with a much more casual attitude. The act of using Standard Japanese in order to conform reinforces the conformist element of the language, and these scenes imply that while Kaoru embodies the open and assertive image typically associated with Kansai people, there is still an element to her that wishes to avoid unnecessarily going against the grain.

Formality (Keigo)

Power Dynamics and Role Changes

One of the most important elements of the Japanese language that, as a result, conveys a unique sociocultural significance is its sliding scale of formality known as ‘keigo’. During the construction of a Japanese identity, emphasis on specifically Japanese virtues, such as a sense of respect and modesty, were seen as characteristic traits, which led to the push for a concept of deferential language, or keigo, being adopted to separate “ugly language” from “beautiful language” (Pizziconi 271). In Japanese, the context of the conversation and the speaker’s goals will change the level of formality used in various ways. For example, employees will use humble and deferential language when speaking to their boss at work. However, when those same employees, along with their boss, are in a meeting with representatives of another company, they will instead use language that puts them all on the same social standing while placing those of the other company on a pedestal. Situations such as these are considered ‘task-based role changes’, and can be created by necessity or choice, with even close friends assuming formality with each other should the situation arise (Obana 254). While keigo is often considered ritualistic, context and interactants’ stances manipulate its usage, enhancing the quality of communication (Obana 248). In Japanese media, keigo is typically used to denote power dynamics without explicitly stating them, as Japanese-speaking audiences are capable of picking up on the linguistic differences between characters. Where a character chooses to speak humbly, deferentially, or casually reveals their subservience or power over another, and even their social standing. In another way, one’s lack of proper honorific language where it should be appropriate suggests another layer of meaning behind a character’s actions. A situation such as this would be more than simply speaking rudely to a superior, as it is possible in Japanese for one to speak amicably while still using improper formality. To not do so would be an act of defiance against societal norms, especially significant in a Japanese story where unity and respect are considered virtues.

As a series set in modern day Japan, keigo usage carries a different impact within the Yakuza series. While a fantasy setting is still capable of utilizing keigo to handle power dynamics and different relationships, it would not carry the same sort of real-world social significance. Furthermore, given that the series takes place within the hierarchy of different yakuza organizations, keigo usage is frequent and oftentimes a very real matter of life or death. For one familiar with the language, any mid-conversation changes in formality are apparent. There are many scenes throughout the series where a yakuza thug will start off speaking informally or threateningly, only to shift to a higher level of formality and deference when their superior walks in, or when they become aware of Kiryu’s own status or legendary reputation, usually out of fear after having been physically overwhelmed. There are also a number of high-ranking characters who come off as menacing and crude that noticeably shift into formal speech when addressing one of the few superiors they answer to, typically their clan’s chairman. Kiryu himself speaks formally whenever the situation calls for it, but he is interesting in that he retains his usual stoic tone while doing so, leaning more towards respect rather than humility. In Majima’s introductory scene in Yakuza Kiwami, Kiryu addresses him as his superior with formal language and a customary bow. In the same scene, he later prevents Majima from attacking someone unnecessarily by physically holding him back, yet he retains his formal language while doing so. Part of adhering to keigo customs is deference to authority, so his defiance in the face of a superior while still using language that gives him the respect his station demands creates an interesting presentation for Kiryu’s character as soon as one of the first major scenes in the series: that he is a man of tradition and culture, but will not compromise on his personal beliefs. More than just his actions or tone of voice, his intentional language use is one of the key elements in the creation of his character.

As a series set in modern day Japan, keigo usage carries a different impact within the Yakuza series. While a fantasy setting is still capable of utilizing keigo to handle power dynamics and different relationships, it would not carry the same sort of real-world social significance. Furthermore, given that the series takes place within the hierarchy of different yakuza organizations, keigo usage is frequent and oftentimes a very real matter of life or death. For one familiar with the language, any mid-conversation changes in formality are apparent. There are many scenes throughout the series where a yakuza thug will start off speaking informally or threateningly, only to shift to a higher level of formality and deference when their superior walks in, or when they become aware of Kiryu’s own status or legendary reputation, usually out of fear after having been physically overwhelmed. There are also a number of high-ranking characters who come off as menacing and crude that noticeably shift into formal speech when addressing one of the few superiors they answer to, typically their clan’s chairman. Kiryu himself speaks formally whenever the situation calls for it, but he is interesting in that he retains his usual stoic tone while doing so, leaning more towards respect rather than humility. In Majima’s introductory scene in Yakuza Kiwami, Kiryu addresses him as his superior with formal language and a customary bow. In the same scene, he later prevents Majima from attacking someone unnecessarily by physically holding him back, yet he retains his formal language while doing so. Part of adhering to keigo customs is deference to authority, so his defiance in the face of a superior while still using language that gives him the respect his station demands creates an interesting presentation for Kiryu’s character as soon as one of the first major scenes in the series: that he is a man of tradition and culture, but will not compromise on his personal beliefs. More than just his actions or tone of voice, his intentional language use is one of the key elements in the creation of his character.

Unique Implications

One common theory about keigo is that its usage carries similar implications of friendliness, approachability, or politeness. However, this is not entirely the case, as keigo usage is meant to accomplish different goals in social situations. Classic notions of ‘polite’ versus ‘impolite’ can be more accurately interpreted as high versus low, weak versus strong, elegant versus vulgar, and so on in how they convey honorific meanings (Pizziconi 270). In Japanese, adherence to keigo is more of a societal obligation, and carries more nuance than simply being polite or respectful in a given interaction. Professor Motoki Tokieda observes that the use of keigo says as much about the esteem a speaker holds addressees and referents as it does about their own personality and erudition (Pizziconi 273). In fact, rather than creating a sense of approachability like a formal English speaker may do, formal language in Japanese works as a “face management” system that contributes to the creation of a social or psychological distance between interactants (Obana 248). In other words, speakers maintain a social distance so as to not risk offending or appearing overly-intimate with their conversation partner. During conversation, strategies may be employed to avoid face-threatening acts by creating distance so as to not overstep boundaries. In doing so, there are certain instances where using honorifics may be considered distant and unfriendly, and the eventual dropping of formal speech may indicate newfound friendship. Considering keigo polite and the lack of it impolite is inaccurate, as the use of crude or casual language and the subsequent lack of honorifics that would come with it may suggest a friendlier presentation, depending on the circumstance. In Japanese media, shifts in language are highlighted or made a point of, and character relationships are able to be seen in a clearer light. Similarly, characters are placed in less-than-friendly situations more often than one would find in real life, so there is a greater opportunity to showcase the different ways in which keigo can be utilized. Without real-world consequences to negative social situations, creators are able to stretch the usage of honorific speech, and the yakuza hierarchy provides a unique setting to aid in this task.

Characters throughout the Yakuza series regularly adopt a threatening tone with others while still maintaining the appropriate level of face-management for the situation. Occasionally, these characters, usually low-ranking grunts, are speaking to superiors in some capacity, and such speech would be expected of them. Other times, the character simply comes off as professional, so they conduct themselves in a formal manner even when saying or performing unsavory acts. While there are many instances of this occurring throughout the series, special mention goes to Ryuji Goda, the primary antagonist of Yakuza 2 and Yakuza Kiwami 2, during the scene in which he attends Terada’s funeral. At this point in the game, with his plans to break away from the Omi Alliance and declare war on the Tojo clan all throughout Tokyo, Goda has been firmly established as the enemy, and has fought Kiryu multiple times up until now. In addition, he speaks in an overly masculine and crude way, with his Kansai dialect only accentuating his rough tone. However, his speech is also one of the main things that contributes to his contradictory presentation during this scene. He arrives at the funeral; uninvited, but in formal dress and a monetary offering in tow to pay his respect. While his intentions are understandably doubted by those present, his use of keigo and honorific speech stands out as an uncharacteristic adherence to societal norms. Yet despite this moment of formality, it is clear that Goda is not being polite, nor is he trying to trick anybody. After being questioned, he claims that he is there solely out of obligation to a former member of his clan, and later leaves without causing any further trouble. Adding to the impact of this scene are dialectical mainstays of Goda’s character shining through, such as his use of masculine pronouns and his Kansai accent resulting in a naturally rough tone, even while speaking formally. All of these elements combine with his jarring, yet socially appropriate, honorific usage without coming off as strange. These unique linguistic elements are presented to the audience without explicitly being stated, providing subtle details for Japanese audiences to pick up on.

On the other hand, Kiryu represents the nuances of keigo usage through his interactions with Goro Majima over the course of Yakuza and Yakuza 2, including their additional scenes together in the Kiwami remakes. Prior to Kiryu’s expulsion from the clan in the beginning of the first game, Majima is his superior, and Kiryu respects him as such. In their first scene together, Kiryu uses honorific language, and even though they get into a disagreement which leads to Kiryu being beaten over the head with an umbrella, he still upholds the level of formality he is expected to. This is not out of politeness or fondness for Majima, but to prevent negative face for both men. Later, when the story places the two at odds, Kiryu drops formal pretenses and takes on much more aggressive, informal speech as they engage in brutal, over-the-top fights with each other. After some time, the two men become friends and rivals, but Kiryu’s speech style with Majima noticeably doesn’t change from his informal usage. While he still refers to Majima by a respectful title of “Majima-san”, he continues to use the same language with him that he did when the two were on opposing sides. Part of this is at the behest of Majima, as in Majima’s reintroduction scene in Yakuza 2, Kiryu initiates conversation with him using keigo only for Majima to brush it aside and insist on more casual conversation. It is noteworthy that in this scene, Kiryu approaches Majima with a large favor in mind, which parallels real-world interactions between Japanese friends who feel as though they are about to impose on each other. Rather than signifying a tumultuous relationship, however, Kiryu’s usage now suggests that the two have grown close enough to where formal speech would no longer be acceptable. The Japanese language is fluid, and can be adjusted in a number of different ways depending on the circumstances. For Japanese audiences, these things have real-world connections, resulting in unique linguistic nuances that are not easily caught by foreign ears.

Gendered Language

Personal Choice

One way in which the Japanese language can reveal how speakers view themselves is through the use of gendered speech, particularly through pronoun usage. Debra Occhi writes that Japanese creators, particularly in written media, don’t tend to describe their heroes and heroines in the same capacity that Western writers do, instead choosing to focus more on the way that the characters talk to each other as a way to paint a picture for the audience (Occhi et al 412). Alongside a large variety of first-person pronouns and endings to use, the language allows great flexibility in inventing and altering new ways of speaking (Teshigawara and Kinsui 39). Among some of the most common first-person pronouns are the masculine “ore”, the boyish “boku”, the gender neutral “watashi”, and the feminine “atashi”, all of which carry their own linguistic implications and are not restricted to specific genders. For example, in Tokyo schools, there are accounts of young girls taking to using more masculine or typically male pronouns as a means of establishing their own identity and rejecting women’s language norms (SturtzSreetharan 254). On the other hand, while “watashi” is typically used by women, it would not be strange for a man seeking a more neutral presentation to use it as well. Notably, gay and lesbian speech styles also take advantage of pronouns to adopt preferred presentations for themselves (SturtzSreetharan 255). Personal pronouns also carry further complexities in regards to their usage. In English, a person may have their own preferred third-person pronouns they would like to be called by, but these are not something easily conveyed to another person without explicitly informing them. However, in Japanese, addressing someone in the third person (i.e. “you”) is considered overly intimate/inappropriate, and reserved primarily for couples. Reference to other persons in Japanese is subject to a variety of sociocultural factors to a much greater extent than in many other languages, which leads to a number of interesting ways that one is addressed and presents themselves (Ono and Thompson 323). Furthermore, using first-person pronouns at all tends to stand out, as even these are typically avoided in conversation in favor of other words to designate speaker and addressee (Ono and Thompson 324). As such, someone making a point of using their preferred pronoun may suggest something about how they wish to come off in a given social situation. In Japanese media, gendered speech is one key identifier of a character’s traits or role in a story. The term “role language” refers to a number of linguistic factors that serve to identify the ‘role’ a character plays in the story through the way they speak. The majority of these linguistic styles, such as “elderly speech” tend to be used only in media, but gendered language is one of the few based in reality. Teshigawara and Kinsui write that these linguistic styles rely on knowledge shared between the creator and audience to effectively develop the story and convey narrative intent (Teshigawara and Kinsui 40-41). These masculine/feminine/neutral identifiers are but another factor that plays into the presentation of a character and how they perceive themselves, details which Japanese audiences are easily able to link to their own experiences.

As a story centered primarily around overly-masculine and violent men, masculine language and pronouns are very common throughout the Yakuza series and are especially prevalent in protagonist Kiryu’s dialogue. Kiryu and other characters’ frequent usage of first and second pronouns “ore” and “omae” indicate a level of aggression and roughness typically associated with “manly men”, especially in fiction (SturtzSreetharan 258). For a series full of characters who are either hardened criminals or regularly finding themselves in brawls, this sort of language is to be expected. Kiryu’s specific usage is interesting in that he uses masculine pronouns even when speaking formally. In Japanese, not only would it be more formal to shift from “ore” to something like “watashi”, it would be even more formal to drop pronoun usage altogether. This is because asserting a social ranking to another in a formal situation may be considered rude or linguistically clumsy, so it is often avoided (SturtzSreetharan 266). Kiryu’s language suggests a level of unavoidable informality, giving the impression that he’s not completely comfortable or skilled in highly formal situations despite adhering to societal norms. However, it also serves as a linguistic representation of how he exudes “manliness” in all situations. By using informal, masculine pronouns with his superiors, Kiryu’s language works with his physical appearance to give off an aura of perpetual masculinity. Kaoru is another notable character in this regard, but for different reasons. In tense or authoritative situations, she often uses masculine sentence-final particles and words, giving her a much rougher image. While she is making a conscious choice here, some of this is owed to her Osakan dialect, as it naturally integrates many informal words and endings found in Standard Japanese. Despite this, Kaoru uses “watashi” when referring to herself instead of a more masculine alternative. During a heart-to-heart with Kiryu in Yakuza 2, Kaoru uses less masculine language and expresses that, while not always showing it to people, she still values her feminine side. The modifiable nature of pronoun usage and gendered words allows for the creation of many different personalities and representations of characters in Japanese media, revealing them to the audience through speech styles alone.

Special mention should also be given to the language’s ability to present transgender characters and gender fluidity through speech. Because of the language’s association with masculinity and femininity over sex and gender, somebody who wishes to alter their presentation to others is easily able to do so, and creators have a variety of tools at their disposal for creating characters. Throughout the Yakuza series, there are a handful of characters who use language to their advantage. Recurring minor character Ako is one such individual, and is most notable for her appearance in Yakuza 2. Formerly the male leader of a biker gang, Ako now presents as female and ekes out a living as the owner of a small bar. Her feminine pronoun usage adds an additional, linguistic layer to her that is otherwise lost outside of Japanese. In another installment, Yakuza 3 includes a side story involving a transgender woman named Ayaka who similarly uses feminine language to alter her image into a more desirable one. Rather than simply providing surface level information, a character’s intentional usage of specific speech styles reveals details about their self-image and motivations in a way that is unique to the Japanese language.

Special mention should also be given to the language’s ability to present transgender characters and gender fluidity through speech. Because of the language’s association with masculinity and femininity over sex and gender, somebody who wishes to alter their presentation to others is easily able to do so, and creators have a variety of tools at their disposal for creating characters. Throughout the Yakuza series, there are a handful of characters who use language to their advantage. Recurring minor character Ako is one such individual, and is most notable for her appearance in Yakuza 2. Formerly the male leader of a biker gang, Ako now presents as female and ekes out a living as the owner of a small bar. Her feminine pronoun usage adds an additional, linguistic layer to her that is otherwise lost outside of Japanese. In another installment, Yakuza 3 includes a side story involving a transgender woman named Ayaka who similarly uses feminine language to alter her image into a more desirable one. Rather than simply providing surface level information, a character’s intentional usage of specific speech styles reveals details about their self-image and motivations in a way that is unique to the Japanese language.

Conclusions

The unique linguistic features of the Japanese language allow for numerous ways in which creators can express details about characters or the sociocultural factors surrounding them. Regional associations of dialects allow for Japanese audiences to easily identify a character’s traits or the role they are meant to play, such as the multitude of Kansai-ben speakers throughout the Yakuza series like Goro Majima and Kaoru Sayama. Dialect also allows for a significant juxtaposition against the standard language and what it represents for a character to speak “normally”, something executed well through Kazuma Kiryu as well as the Tojo Clan in their conflict with the Omi Alliance. The language’s unique system of formality carries social complexities that help display power dynamics, such as those within the yakuza, as well as giving meaning to a character’s actions when they defy societal norms depending on their usage or the lack thereof. Finally, the language allows for the portrayal of masculinity and femininity to be altered, which reveals how characters view themselves or wish to be viewed by others. The sociolinguistic elements of Japanese are capable of subtly revealing details about a character or the culture in unique ways that native audiences are able to naturally pick up on. Many of these details can be lost in translation or require some sociocultural knowledge beforehand for non-native speakers or foreign audiences to properly understand, but they are valuable additions to a story that reflect the intent of the creator, and should be preserved and taught as such.

One area I believe deserves further inquiry is the significance of Standard Japanese in media, especially when utilized alongside characters who speak a dialect. Studies show that protagonists are typically not created to speak a dialect unless their story takes place in a particular region, which suggests a link to representing a national identity through these heroes. However, while there are studies that discuss the meaning behind deviations in different characters’ speech, there is a lack of research dedicated to the study of what it means for a character to speak “normally”. Additionally, further study on keigo in media would likely reveal some of the significance found in certain power dynamics. Keigo usage is subject to numerous exterior factors in conversation, so extra focus on what it means for characters in fiction to adhere to or defy these norms would assist with revealing narrative intent. The vast majority of sociolinguistic study over the Japanese language is kept within Japan and written for Japanese audiences. As such, any effort made to help bring this research to foreign scholarly discussion would contribute to a deeper appreciation of Japanese media overseas.

Matsumoto, Y., & Okamoto, S. (2003). The Construction of the Japanese Language and Culture in Teaching Japanese as a Foreign Language. Japanese Language and Literature, 37(1), 27–48. https://doi.org/10.2307/3594874

Obana, Yasuko. (2019). Politeness. Routledge Handbook of Japanese Sociolinguistics (1st ed), 248-260.

Occhi, D. J., Sturtzsreetharan, C. L., & Shibamoto-Smith, J. S. (2010). Finding Mr Right: New looks at gendered modernity in Japanese televised romances. Japanese Studies, 30(3), 409-425. https://doi.org/10.1080/10371397.2010.518605

Ono T., Thompson S. (2003). Japanese (w)atashi/ore/boku I: They’re not just pronouns. Cognitive Linguistics, 14(4), 321-347. https://doi.org/10.1515/cogl.2003.013

Pizziconi, B. (2004). Japanese Politeness in the work of Fujio Minami. SOAS Working Papers in Linguistics, 13, 269-280. https://eprints.soas.ac.uk/54/1/Pizziconi_1.pdf

Rahardjo, Hardianto. (2020). Linguistic Stereotypes toward Osakan Dialect Speakers in Fiction. Widyatama Journal, 1-12.

Sakamoto, H. (2018). Yakuza Kiwami 2 [Video game]. Ryu Ga Gotoku Studio.

Sato, D. (2010). Yakuza 3 [Video game]. Sega CS1 R&D.

SturtzStreetharan, C. (2015). “Na(a)n ya nen”: Negotiating Language and Identity in the Kansai Region. Japanese Language and Literature, 49(2), 429-452. Retrieved August 7, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/24615146

SturtzSreetharan, C. L. (2009). Ore and omae: Japanese men’s uses of first-and second-person pronouns. Pragmatics, 19(2), 253-278. https://doi.org/10.1075/prag.19.2.06stu

Teshigawara, M., & Kinsui, S. (2012). Modern Japanese “Role Language” (Yakuwarigo): fictionalised orality in Japanese literature and popular culture. Sociolinguistic Studies, 5(1), 37–58. https://doi.org/10.1558/sols.v5i1.37

Twine, N. (1988). Standardizing Written Japanese. A Factor in Modernization. Monumenta Nipponica, 43(4), 429–454. https://doi.org/10.2307/2384796

Yoshida, K. (2017). Yakuza Kiwami [Video game]. Ryu Ga Gotoku Studio.